Wind turbine blades, railway tracks, bridges and houses featuring concrete constructions of every shape and form. These everyday items and materials are often the work of engineers, with their wonderful ideas and intricate calculations. But calculations are not enough in and of themselves—the materials must also prove their worth in a simulated reality before they are applied in the real world. This is where the craftsmen in the DTU Civil Engineering workshops display their expertise, which is second to none.

Their workplace is not exactly calm and predictable. In the giant hall, the ceiling is ten metres high, techno-like green towers shoot up everywhere, and the floor is not even in contact with the ground. It is actually a metre-thick clamping plate resting on columns, where every type of test set-up you can possibly imaging can be secured so firmly in place that it can withstand many tonnes of pressure, pull and vibrations.

The columns are there to prevent the entire building from vibrating along with the test elements, and to stop pens and pencils rolling off desktops in the offices. The forces applied are often so great, however, that the pressure can be felt through the ground. Moreover, when the materials finally do buckle and crack under the pressure, the do not give up quietly ...

Almost like a family

In the basement, the concrete mixer is constantly in operation, and wherever you look you are sure to see young people working to complete their individual concrete blocks, which they can then experiment on up in the hall. For the past three years, the concrete realm has been the purview of Per Leth. Per has plenty to do here, because there are a great many young people working on projects, and they all want advice and guidance.

"The young people are all so positive, and it’s fun to track their development. Quite a few of them come back to say hello after they have had their first taste of life in the real world. I’ve even met some of their parents."

Per Leth, Concrete Technician, DTU Civil Engineering

“My boss thinks I get too involved, but he can keep on talking about that until he’s blue in the face. If people need help, I’ll help them. Some students are simply not at all good with their hands, so they need someone to guide them. No-one is going to see their project come off the rails as long as I’m here,” says Per, quietly but with conviction.

It is no wonder that the students come to like him after spending weeks or months in the concrete casting department, talking about everything under the sun.

“My colleagues may be a little jealous of me,” he says with a smile, before making it clear that although he is extremely busy—almost stressed at times—he loves his job.

“The young people are all so positive, and it’s fun to track their development. Quite a few of them come back to say hello after they have had their first taste of life in the real world. I’ve even met some of their parents.”

Workshop with a wooden floor

In order to be able to make a concrete cast, you need a mould; and this is where Steen Lenskjold Jensen, an experienced joiner, comes into the picture. Up in the only room in the building with a wooden floor, he takes orders for moulds in all shapes and sizes, drilled out to accommodate pieces of rebar. Occasionally, he also finds time to cut a stack of wooden blocks destined for use in the fire laboratory across the road. He can even make iron items, if the smiths are fully booked. This is what the craftsmen here do; they are a largely autonomous group with the capacity to cover one another’s areas.

Steen has been at DTU for 18 years, having ‘put four master joiners in the ground’, as he poetically expresses it.

Steen Lenskjold Jensen

“This is the perfect place for me. I have the chance to work with both wood and metal, I assemble pipes and cables, and get to repair all kinds of things. I spent a whole year renovating offices. In fact, there isn’t an office in the place I haven’t been in to install something or other. It’s been a lot of fun, and it’s never dull,” says Steen, who, in the same way as many of his colleagues, contributes knowledge about his craft to the three-week courses. And he’s an absolute machine when it comes to the final execution of the orders.

“For example, I received a drawing for this large mould,” he says, pointing to his latest project, which measures one and a half metres by one and a half metres and is 25 cm high. “The students thought that it would need crossbeams for support because it was so tall, but it is sturdy enough without them, so I won’t be putting them in. This is the kind of thing I get to decide.”

Data needed

A monitor and mouse are the only things to suggest that the piece of furniture in Christian Rasmussen’s office is actually a desk. Every inch of it is covered, making it seem impossible to do any work at all on it.

Christian Rasmussen

“One thing is for sure, I rarely write long sentences. But everything important is placed here in front of the keyboard—and it gets less and less important as you work your way out. I would find it too stressful to take things out and put the assignments up on the board,” says Christian with a gentle smile.

Christian is a qualified electronics technician and employed as an engineering assistant. He does not work exclusively with electronics, however, but applies all his mechanical skill to setting the experiments up in test machines and linking them to measuring devices and data loggers to make it possible to track and document everything that takes place, second by second.

“The assignments span the full range from simple ones involving applying pressure to concrete samples to find the breaking strain, or subjecting rebar to tensile tests to establish properties of the steel, to more special experiments centred on new types of concrete,” he explains.

It is often not until they talk to Christian that the students actually become aware of what they need to do, and he spends much of his time pinpointing the simplest possible experiment set-up.

“The trick is to organize the assignments so as to ensure we use as few materials and as little time as possible, without this affecting the ultimate purpose: calculating the actual properties of the finished construction.”

Fewer hands to do more work

Christian has ‘only’ been at DTU for 15 years. Michael Ramskov, assistant engineer, and Keld Plougmann, workman, have both celebrated their 38

th anniversary here.

They both joined the department on 15 April 1977; Michael having completed his apprenticeship at DTU and spent several years working in the private sector, and Keld having sailed all over the world with Maersk and ØK, and having built ship engines at B&W.

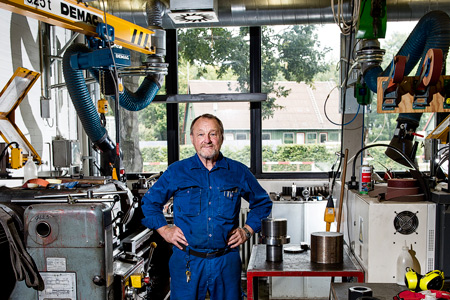

Keld will turn 70 in October and has cut his working week to 20 hours. Otherwise, he is carrying on regardless, turning, milling and welding all the bits and bobs used to make sure the samples sit exactly where they should in the set-ups.

Keld Ploughmann

Michael does more than work at the machines ; he also maintains an overview of the projects, takes care of the workshop finances, and keeps in touch with external companies that deliver the parts that are too large for the workshop’s own machines. And he is an extremely conscientious OHAS representative, who makes sure the users have everything they need to work safely in the workshop.

“Twenty years ago, we had twice as many craftsmen and half the number of students, and we also handle a range of assignments for external customers. If the young people didn’t do some of the work themselves—in the foundry, for example—we simply couldn’t produce as much as we do.”

“Back in the day, the associate professor would come over and hand us the assignments, so we hardly ever saw the students. The situation is quite the opposite today. It’s great to meet all these enthusiastic people, brimming over with ideas and zest. You sort of get caught up in their ideas and draw energy from their infectious enthusiasm,” he says, neatly expressing the general atmosphere in the workshop.

Article in DTUavisen no 8, October 2015.