Mariann Albjerg has named her home in Denmark ‘MECO’, which is standard shorthand for ‘Main Engine CutOff’. And on the window sill stands a 1:200 scale model of the space shuttle Challenger. Otherwise, there is little to reveal that you are visiting the Dane who held the highest position ever at NASA.

Mariann Albjerg moved to the United States with her husband in 1979. In contrast to many of the women in her circle of friends, she immediately set out to find a job. Having trained as a chemical process technician, and with experience from Haldor Topsøe, Radiometer and Danmarks Tekniske Højskole (which later became DTU)—backed by boundless interest in space travel—it was only natural for her to try her luck with NASA.

And so from 1979 until 2010, the year before the termination of the shuttle programme, she was a fixed member of the team. Mariann was involved in around 50 of the 133 successful flights by Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour.

“NASA JSC was keen to take on minorities, and as a woman with a university education, I was a minority that ticked pretty much every box, so I was given a fantastic chance. My first two years were taken up with training and courses at the Johnson Space Centre, which was also known as ‘The College for Manned Space Flight’, before I was taken on as an Aerospace Engineer specializing in manned space travel,” she explains.

Ten years in mission control

"I feel really privileged. For 30 years, I played an active role in the most exciting period ever in the history of manned space exploration. And it’s incredible to come back home and be a part of DTU Space, because it’s like NASA in miniature. The high level of expertise, the attitude and the approach to the work are all the same."

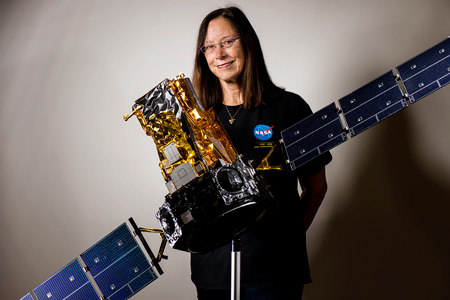

Mariann Albjerg

Mariann Albjerg ushers us into a little hallway. It is her wall of memories, covered with framed photographs, autographs and patches, which are awarded to people who have made a special contribution to a given flight.

“I’ve hung it all in here, because it’s mainly of interest to me,” she says.

However, for anyone who has taken an interest in the shuttle programme, this is not strictly true. There are autographs and personal messages from a number of astronauts, including Dick Scobee, Captain of the Challenger. There is also an ‘Employee of the Quarter’ award from NASA.And a small framed American flag that was on board Columbia during its second flight. Not to mention pictures of the containers the space shuttles used to carry scientific experiments—and which were Mariann Albjerg’s responsibility more than 30 years ago in Houston, Texas.

When Columbia became the first space shuttle to head into space on 12 April 1981, Mariann Albjerg was present in the control room as a part of her training. For its second flight, in November of that same year, she was responsible for its payload—the scientific experiments that Columbia carried into space.

Those flights marked the start of ten years in mission control, where she was involved in many of the scientific experiments that have expanded our knowledge of the universe. She herself highlights theLong Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), whose objectives included examining the effect zero gravity has on solutions of biological materials and the precipitation of crystals.

In 1999, she moved to NASA’s headquarters in Washington DC, where she held the position of Flight Integration Manager; this meant that she held overarching responsibility for—and selected—the scientific experiments on the space shuttles.

Two tragic accidents

The objective of the shuttle programme was for the space shuttles to fly back and forth between the Earth and space, maintain satellites, and carry all the parts required for the International Space Station (ISS). But the shuttles are no longer flying. Largely because things went horribly wrong on two occasions. The first time was with the space shuttle Challenger.

“The whole plan had fallen apart. Challenger should have gone up before the end of 1985, so there was enormous pressure from Congress for the shuttle to launch,” relates Mariann Albjerg.

“I met the crew ten days before they went up. They wanted to sign a picture for me, but I asked them not to, saying I’d rather wait until they came back. They never did.”

When Challenger finally launched from the Kennedy Space Center on 28 January 1986—with a crew including her good friend Dick Scobee on board—Mariann Albjerg was on holiday on Hawaii. Temperatures in Florida were below freezing, and a rubber ring intended to seal the right booster rocket was not completely tight. One minute and thirteen seconds after launch, almost 200 million litres of fuel burst into flame. The space shuttle disintegrated in the inferno. Challenger and its crew never escaped the Earth’s gravity.

On 1 February 2003, it is the space shuttle Columbia—which Mariann Albjerg was involved in sending into space 22 years earlier—that falls apart after 28 successful missions. A piece of insulation on the fuel tank about the size of a suitcase tears loose during take-off and strikes the left-hand wing of the shuttle.

The tiles designed to protect Columbia as it re-enters the atmosphere are damaged in the accident, and when the shuttle begins its descent back to Earth, hot gases force their way into the wing, destroying it from the inside. The space shuttle becomes unstable, and pieces of wreckage are spread from California to Texas.

Main engine cutoff

Mariann Albjerg insists that both accidents should have been avoided, but goes on to explain that everyone at NASA was aware of the risks.

“None of the astronauts stepped out of the queue after either the Challenger or Columbia accidents. We knew it was dangerous, and precisely because the astronauts had that mindset, it was an attitude we all shared. In my opinion, they demanded that we continue. That was what they gave their lives for. And even though there were two accidents, I still think we should have kept going. They were way ahead of their time in every respect,” concludes Mariann Albjerg.

The shuttle programme was finally terminated in 2011, and NASA has not launched a manned space flight since. Mariann Albjerg still keeps a keen eye on space exploration from her home in Rungsted, however.

“I feel really privileged. For 30 years, I played an active role in the most exciting period ever in the history of manned space exploration. And it’s incredible to come back home and be a part of DTU Space, because it’s like NASA in miniature. The high level of expertise, the attitude and the approach to the work are all the same. My heart will always belong to NASA, and I’m now looking forward to helping develop the great partnership between NASA and DTU Space,” she says.

“When you fly space shuttles, you have a flight plan—and I do, too. So when I bought my home here in Rungsted, I saw it as my launch. Now I’ve made it into orbit and the main engines have shut down —which is what we call ‘Main Engine CutOff’ or ‘MECO’. That means you’re in space, heading for where all the fun starts ...,” she concludes.

|

|

Mariann Albjerg was born on 8 March 1947.

|

- 2010: Retires and moves back to Denmark. Becomes a member of the DTU Space Advisory Board

- 2001: Technology Development Manager, NASA Earth Science Technology Office

- 1996: Shuttle programme Flight Integration Manager at NASA’s headquarters in Washington DC

- 1989: Granted American citizenship, taken on immediately by NASA, JSC. Program Manager, International Integration for Space Station

- April 1981: Working in Mission Control Center when Columbia becomes the first space shuttle launched.

- March 1981: NASA Ellington Field. Takes part in parabolic flights including periods at zero gravity (0 G)

- 1979: Employed at NASA Johnson Space Center/Ford Aerospace in Houston as an engineer in the Flight Operation Division

- 1979: Employed at Danmarks Tekniske Højskole (now called DTU) as a chemical process technician in Danchip and Phys. Lab. III

- 1968: Graduates as a chemical process technician from Danmarks Teknologiske Institut.