One thousand DTU students are now live guinea pigs in a social network experiment whose scope and scale are unparalleled. The students have all been given a free smartphone. In return, they have agreed to allow researchers from DTU and the University of Copenhagen to collect data on all their social interactions in the form of e-mails, text messages, online social networks, and phone calls using specially developed smartphone software.

The project does not collect the content of the communication, but rather information in anonymized form about where the students are located in time and space and with whom they are communicating—i.e the test subjects appear only as numbers and data points.

Despite anonymization and secure data handling, the researchers have been surprised to discover how much knowledge about people and their behaviour can be extracted from an ordinary smartphone. What began as a physicist’s idea of studying dynamics in networks has thus developed into a research project focusing on how to secure personal data, and how we relate to the fact that we are all data producers in a digital world forged by the new technologies.

World’s most awesome data sets

“I’ve always been interested in networks, and when smartphones became a household item back in 2011, I suddenly had the opportunity to use the small, powerful computers—which phones are—to capture all channels and ways we humans communicate, and in so doing create a data basis for research in social networks of a quality hitherto unseen. Social networks are highly dynamic, and we know very little about how such a network actually looks in real life. With the dataset we now have, we can examine networks as social events in time, and describe in mathematical terms how processes work—e.g. how information is disseminated,” says project initiator Sune Lehmann, Associate Professor at DTU Compute.

Sune Lehmann quickly realized that the information from the students’ phones had a far wider application than merely describing the mathematical regularities of networks.

“One of our first major discoveries was how much more we suddenly knew about traffic in Copenhagen and the surrounding area. If you activate 1,000 small sensors and measure the position of the phones every 20 seconds, 24/7, you gain an extremely accurate picture of the main traffic routes and motorist’s traffic habits. So now we suddenly have one of the world’s best mobility datasets. On the basis of our data, new research projects on the design of transport systems are currently being developed. And this is just one example of how rich a data source smartphones and the set-up we have created actually are,” says Sune Lehmann.

|

The individual smartphones’ position can be traced all over the world.

|

|

Illustration: Shutterstock |

Jubilant social sciences

When Sune Lehmann wanted to scale up his original project from 200 to 1,000 phones, he teamed up with researchers from the University of Copenhagen. Under the title ‘Social Fabric’, the unique dataset is now the focal point of a major interdisciplinary research project in which philosophers, economists, anthropologists, psychologists, and researchers in public health together with computer experts and network researchers from DTU are studying all possible aspects of human social behaviour. And while the data volume is daily growing at a rate of 50 – 100 GB, the list of research projects that will benefit from the new data also grows longer and longer.

“What’s unique about this experiment from a social scientific perspective is the fact that we have gained access to valuable data material that we typically lacked the technical expertise to generate. By working with engineers and data researchers from DTU, we are able to generate data on a scale and with a level of detail we are quite unaccustomed to,” explains David Dreyer Lassen, professor of economics and the anchorman responsible for the University of Copenhagen's participation in the project.

Creatures of habit

“The data we receive from mobile phones tells us a great deal about the participants’ daily routines. In fact, we have been surprised to see the degree to which the participants’ lives fall into fixed routines and is thus easy to predict. Humans are basically creatures of habit—a fact clearly borne out by their smartphone data,” explains David Dreyer Lassen.

But what is it like as a project participant to have your habits mapped down to the smallest detail? For DTU student Johan Rojek, who participated in the experiment for a period, the whole process was quite undramatic:

“Before I signed up for the project, I looked carefully into the whole thing and considered the impact of having all my actions logged on my phone. But when I saw that they were on our side, so to speak, and that the project among other things actually focuses on privacy and data security, I thought it was an exciting project to be a part of, and I didn’t spend much time thinking about being monitored in the name of science.”

|

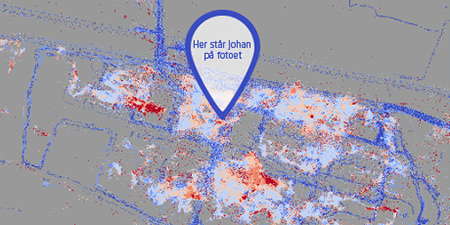

Johan Rojek in front of DTU’s main entrance. His smartphone has already registered his location.

|

|

Photo: Iben Julie Schmidt |

In reality, we are all in the same boat as the participating students.

“This kind of data collection is already being carried out by companies such as Google and Facebook. The difference is that we never get to know what they use the data for, and we may not be giving enough thought to what we are agreeing to when we accept their terms and conditions,” says Sune Lehmann, who adds:

“We have therefore made it a project priority to provide information about what data companies have access to, and how these data may affect our privacy and data security.”

|

Smartphone movements automatically generate a map of DTU’s campus in Lyngby. The red areas, for example, indicate the canteens and large classrooms where there is a high concentration of students. The blue ‘droplet’ indicates Johan’s position in the photo above.

|

|

Illustration: SensibleDTU |

Next step: a whole city

“The project has been running for more than three years, and we have learned a great deal. Nonetheless, it is easy to feel that we’re only scratching the surface. We have already collected data to keep teams of researchers busy for many, many years, but the next step, of course, is to expand our dataset to cover an entire city or a whole country to make our data more representative and to reap the full benefits of this type quantitative data, which offers such fundamental insights into human habits and behaviour,” says Sune Lehmann.

Article from DYNAMO no. 42, DTU's quarterly magazine in Danish.