A new DTU energy model has been used to reality-check the climate policy goals announced by the Danish government and six political parties.

The conclusion is that many of the parties are well underway, but that a number of questions of principle need answering for the goals set out in the Paris Agreement to be fulfilled.

Researchers from DTU Management have developed a technical/economic model for calculating contributions from energy systems and technologies towards achieving particular carbon emission goals. The model can, for example, say what the implementation of various technologies would cost, how much pollution is going to be generated as we work towards the goal, and how soon we can, realistically, start using new technologies and fuels.

The model analyses also factors in the Danish energy tariff system, calculating resulting changes and associated revenues. Based on input about fuel prices, the prices of technologies and the parties’ political ideas about, e.g., subsidies, taxes, offshore wind power tenders, the phase-out of diesel cars, etc., the model identifies the cheapest combination of technologies in all sectors.

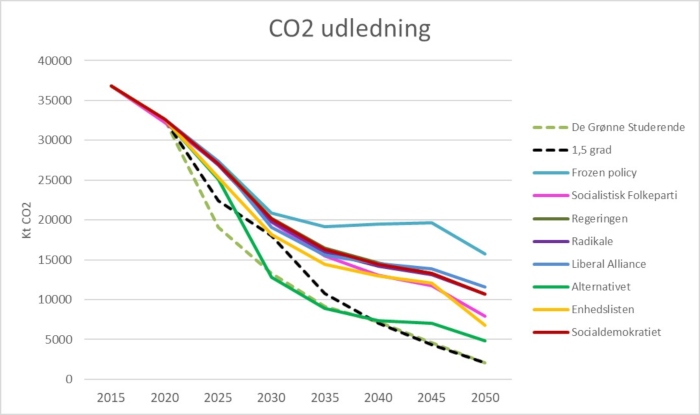

“Using the new model, we have tested the climate goals of the Danish government, the Socialist People’s Party, The Alternative, the Danish Social-Liberal Party, the Liberal Alliance, the Social Democratic Party, and the Red-Green Alliance against the parties’ concrete initiatives. We have done so by comparing the goals with the defined activities and concrete figures,” explains Kenneth B. Karlsson, Head of Energy Systems Analysis Group at DTU Management, who is one of the driving forces behind the model.

Parties fairly aligned

One of the main conclusions is that in so far as the period up until 2030 is concerned, the ideas of the six parties and the Danish government are not nearly as disparate as one might expect. However, there are certain challenges which the parties need to address if Denmark is to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

Fig. Snapshot from 5 April 2019.

“From having been driven by political plans, the transformation of the energy system now depends increasingly on politicians not getting in the way of the technological advances. The transformation is moving ahead at a pace, and businesses have come on board. According to the model, some of the challenges the politicians must address are whether it is acceptable to rely on large-scale imports of biomass in future, how to accommodate the expansion of solar and wind power, how soon fossil fuels can be phased out of the heavy-goods transport sector, and how to ensure the requisite system integration for optimum resource utilization,” says Kenneth Karlsson.

"We would like to democratize the process, so that anybody interested can see the calculations for the various political scenarios."

Kenneth B. Karlsson, DTU Management

In other words, legislative and political decision-making processes pose a particular challenge when it comes to meeting the 1.5 degree goal.

The results presented by the model are not static, but change in step with the updating of underlying assumptions, knowledge, and interpretations of policy measures. Therefore, which party looks most climate-friendly could also change. The more concrete the parties are in formulating their climate action plans, the more accurately the model can calculate the scenarios.

The model covers the electricity and district heating sector, buildings, industry, and transport, including ships and aircraft. However, it only calculates carbon emissions and no other greenhouse gases, like emissions from agriculture, so for now it covers only just over 80 per cent of total emissions of greenhouse gases in Denmark.

More open debate

Kenneth Karlsson urges all politicians to use the model to perform regular reality checks of their political goals.

“Setting realistic climate goals is complex because of the many mutually dependent factors at play. We are therefore very happy to help calculate specific scenarios, should the politicians, NGOs or journalists need our assistance. Verifying the energy policy of any one political party does not take more than half a day or so,” he explains.

“Often, energy models are like black boxes into which the parties feed their assumptions, and which then produce a result. We would like to democratize the process, so that anybody interested can see the calculations for the various political scenarios. We hope the tool will be welcomed by politicians and lead to a more interesting and open debate with opportunities for commenting on the underlying assumptions and future goals,” says Kenneth Karlsson.

- Expansion of offshore and onshore wind power.

- Utilization of surplus heat from bio-refineries, the manufacturing industry and data centres.

- Large heat pumps to replace central and local CHP plants from 2030.

- Large-scale investments in solar cells on rooftops and solar power farms are needed.

- Electric vehicles will be the cheapest and probably the dominant vehicle technology—how do we support this development?

- Biomass imports could pose a huge problem. Another important question is whether to build bio-refineries in Denmark or import the fuels.

- Energy savings in buildings and industry.

- Storage of electricity.

- Carbon capture and storage.