It is a bit of a mystery what happens when a star 100 times more massive than the Sun explodes in a sea of lights in the far universe.

But researchers have now identified a special shell around such a star and is therefore one step closer to understanding the giant starbursts. The discovery was recently published in Nature Astronomy.

Back in 2016 and 2017, researchers—Earth-based telescopes—discovered some inexplicable things with light emitted from a giant exploding star deep in space, which they were observing. The star was an extra powerful supernova—called a ‘superluminous supernovae’—i.e. a super bright surpernova.

The light from this supernova—named iPTF16-eh—produced a kind of echo.

“In short, it turns out that a shell has formed around the star, which reflects the light emitted by the star when it explodes into a supernova. We have registered what we call a light echo and have thus proved that there is a shell around the star," says Giorgos Leloudas, Senior Researcher at DTU Space. He is co-author of an article about the discovery, which has just been published in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy.

The light from iPTF16-eh was recorded by the Intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (iPTF), which is a survey using a number of telescopes installed in California to automatically monitor selected areas of the night sky.

Superluminous supernovae

Researchers have only investigated the superluminous supernovae in detail for the past ten years, and only around 100 of them are known.

When a big star explodes, it is called a supernova. Here, huge amounts of energy and light are emitted when the star collapses as it does not have any more elements that can merge. Then, a neutron star or a black hole is typically formed.

The superluminous surpernovae are far more intense, and the explosion process also differs. Their mass is far greater than that of ‘ordinary supernovae’ and more than 100 times larger than the mass of the Sun. They emit 10 to 100 times more light than ordinary supernovas when they explode.

The shell surrounding iPTF16-eh turns out to be formed by material ejected from the star about 30 years before it exploded and became a superluminous supernova.

“We still don’t understand the mechanism behind the star explosion. But now that we have found out that a shell is formed around the star, we are one small step closer,” says Giorgos Leloudas.

“Now we know that they can cast off large layers of their material in the late stages, just before they become supernovae, and that the light emitted is related to the interaction between this material and material from the star itself.”

"We have registered what we call a light echo and have thus proved that there is a shell around the star."

Girogos Leloudas, senior researcher at DTU Space

The light is reflected and produces an ‘echo’

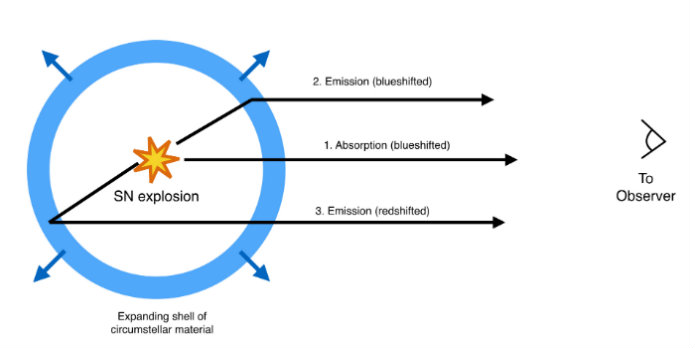

The researchers have looked into the light emitted by the explosion. When it hits the shell, it is reflected so that its wavelength is shited—in the form of redshift and blueshift, respectively—when heading towards Earth, where the telescopes have captured this. The light therefore reaches the Earth—slightly offset in time—depending on where it is deflected in the shell—like a kind of ‘light echo’.

By taking this shift into account, it has been possible to demonstrate both that a shell has been ejected by the star 30 years before the explosion took place and its approximate size.

DTU Space is among the world leaders in this new field and is establishing a research group in the field.

“Research in superluminous supernovae is now really about to get off the ground, so many exciting discoveries are waiting ahead,” Giorgos Leloudas says.

According to the main author of the article in Nature Astronomy, more is going to happen with iPTF16eh:

“The fun isn’t over yet. In about ten years, the material cast off by supernova will catch up with the shell surrounding it and collide with it. It should make it light up again, and it can teach us even more about this spectacular explosion,” Ragnhild Lunnan writes in an article on Nature’s website.

The illustration shows how the light from iPTF16eh forms a ‘light echo’ when it is detected on Earth, as some of it is delayed by the ‘shell’ formed around it. Some of the light passes directly through (1). Some of the light is reflected, as it hits the shell at an angle in relation to Earth and is blueshifted (2). In addition, some light is reflected from the rear part of the shell to Earth, which causes a redshift (3). Illustration: R. Lunnan/Oskar Klein Centre, Stockholm University.

Main photo: Iair Arcavi, Courtesy PTF/Caltech.